Welcome to the Boardroom: Your Second Career

Executive managers who join corporate boards as directors are often unprepared for the transition and fall out of favour quickly. To make the shift successfully a strategic vision is needed.

As a non-executive director on a number of top level boards including Rio Tinto, BG Group, and Vallourec, where she holds the position of chairman of the Supervisory Committee, Vivienne Cox (INSEAD MBA ‘89D) is a fine example of an accomplished senior executive who has made the successful transition to director status.

In a recent interview with Herminia Ibarra, INSEAD Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cox admitted the transition was not without its surprises. “I don’t think I fully understood that I was actually stepping into a second career,” she notes.

“I thought I was leaving my BP career and that these (new roles) would be interesting things to keep me active in the business world.”

The shift, she told Ibarra, required a different set of skills and a change in modus operandi.

“What I loved about my [earlier] executive role was having teams of people around me (and) businesses to run and lead and manage in the sense of giving real direction and focus to the activities.

“What I’ve learned now, is that I really love asking the questions that help other people frame that.”

Making the transition

Typically in organisations CEOs exhibit biases, but challenging the status quo does not always come easily. “Everything enforces what we already know,” says Cox noting that sometimes checking where the downside risks might be in future strategic moves can be eschewed all too readily by senior management.

As a non-executive director however, she has the opportunity to encourage top managers to face these difficult questions. “To sit on the board and say ‘but have you thought about what could go wrong, have you thought about what the risks are?’ Just having a different perspective and asking the right questions [is beneficial].”

So how do you successfully make the transition from senior management to sitting on the board?

Cox’ advice is, “Firstly, don’t take it lightly.” Serious and thoughtful preparation is vital as is taking advice from experienced board members. “Think about taking on a role in a not-for-profit, for example, or spending as much time as you can interacting with your own board and observing their dynamics and processes,” advocates Cox. The important thing is to take small steps as you prepare for your new role.

Sustainability a board responsibility

It also takes vision. Cox comes from a long and illustrious career in oil and gas. During her 26 years with BP she spearheaded the company’s US$6.7 billion investment into renewable energy at a time when shareholders didn’t value renewables in the same way they did oil and gas.

For Cox, there is no distinction between long-term sustainable endeavours and short-term profitable business. When quizzed on the role boards should take on matters of sustainability, Cox insists the issue should be looked upon as a strategic responsibility at an organisational level, not just a CSR department’s responsibility. “If you are running your business in the right way (not only for the company but also for the country you’re operating in, and for the planet that you’re part of) this is all adding value and one of the real benefits is the motivational effect it often has on the people. It is also a key factor in retaining good talent.”

As board members face an ever-growing list of regulations and increasing pressure from activist shareholders, it is helpful for them to understand the expertise they are bringing to the table and to make sure their voice is heard. Diversity on boards is healthy and adds hugely to a company’s strategic decision-making process, insists Cox. “Good dialogue, honesty, openness and transparency” are all critical elements. She isn’t alone in this opinion. Recent research by Solange Charas also espouses the belief that the quality of board members’ interactions are crucial to a board’s success.

Female diversity is an important dimension of that board diversity, Cox says, noting that in her experience women are “less directive, they are better at listening and better at bringing in others. They therefore complement the discussion powerfully ― provided that they’re in an environment where they’re confident to do so and have the space to do so.” For her the magic number of women on a board is three. This bears out earlier research on the critical mass on corporate boards which found any less than three females resulted in the women still being marginalised and regarded as distinctly “female” directors. Once three join the board, their individual contributions are viewed at face value without pre-conceptions.

The more diverse a board is, the better able it will be to reconcile difficult choices and align these choices with the company’s business objectives. Boards will also be more nimble in the face of growing stakeholder power. The way to contribute to this process as a potential board member is to know the value you add from your years of management and life experience.

With this in mind, is the time ripe to get your second career underway?

Herminia Ibarra is Professor of Organisational Behaviour and The Cora Chaired Professor of Leadership and Learning at INSEAD. She is also the Programme Director of The Leadership Transition, part of INSEAD’s portfolio of Executive Education Programmes

What Makes a Good Chairman

Good chairs know whom they are accountable to and it’s not shareholders or employees.

“I am a member of the founding family, but I know that as a chairman I work for the company, for its long-term sustainable development, not for the family. I am aware of the family’s interests, I take them into account as I do the interests of other stakeholders, but I put the company’s interests first”.

This recent comment from a programme participant of Leading from the Chair, our executive development programme at INSEAD for board leaders, was a response to a question we put to the 20 chairs from 13 countries we had in the classroom; “What makes a good chair today?” Collectively, we developed some interesting insights.

Reflecting on research findings, cases and simulations, the group agreed that the right mindset and sufficient time commitment (30-40 days a year) are more important than specific personal attributes such as tenacity, extraversion, public speaking or debating facility. Yet the participants identified three characteristics of good chairs; personal humility; listening, while challenging and supporting the board and the ‘guts’ to do what is right for the company.

It starts with humility

A good chair knows who she works for and is ultimately accountable to the organisation of which board she leads. Not its stakeholders – shareowners, customers, employees, executives, but the institution itself.

A good chair unequivocally understands her role – to lead the board of directors. The board is a very special institution at every company – it meets

only a few times a year for a few hours, but makes decisions that define the organisation’s destiny for years to come. It is an expensive institution – one

hour of the board’s time costs a company listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) upwards of US$100,000. To lead the board is a challenging and noble undertaking, but many chairs are not content with this role and try to

move beyond it to leading the company, leading its management team or leading its public relations’ efforts. The participants agreed that in most cases such duality reduces the chair’s effectiveness in executing her core role – to lead the board. The consensus was that a good chair gets the board to work seamlessly before taking on any additional roles.

A good chair understands that first and foremost she is accountable to people who elected her – board members, but also recognises the importance of other organisational stakeholders.

Challenge and support

A good chair knows what the mission of the board is, how to stay focused on it and how to measure progress. No two companies are alike and the board’s mission may vary from one organisation to another depending on its maturity, regulatory context, industry and ownership structure. For example, at privately-held start-ups, boards usually provide a lot of strategic advice to management and help to secure external resources (enterprising function) while at mature public companies they focus on executive compensation and evaluation and controls (monitoring function). However, the group believed that every board of directors should concentrate on long-term value creation and, especially, value (and company) protection. A good chair understands that and focuses on effectiveness rather than the efficiency of her board’s work – the decisions it makes are far too important to be rushed.

A good chair organises the board’s work inside and outside the boardroom. She makes sure the board tackles issues which are strategic and material for the organisation and mature for discussion. A good chair frames the discussion questions in such a way that directors are clear about the context, understand important facts and assumptions, see challenges and risks for the organisation and find specific solutions for them. A good chair makes sure board resolutions are concrete, actionable and understandable for people who will execute them. She also organises the follow up process, tracks progress and makes sure the board is aware of it.

A good chair sets clear behaviour standards for directors and ensures adherence to them by providing feedback, encouraging appropriate behaviours and dealing with misconduct in a strict, but constructive manner. She resolves conflicts at the board by being fair, consistent and attentive to individual board members, but keeping in mind her ultimate mission – long-term interests of the organisation.

A good chair effectively represents the board in relations with its key stakeholders – shareholders, regulators, management, communities and ensures that directors are fully informed, but does not replace the company executives in their dealings with the stakeholders unless this responsibility has been explicitly given to her by the CEO and directors.

Doing what is right

If crisis strikes a good chair… well, she remains a good chair. She thinks about the interests of the organisation, takes a long-term view, and sticks to her mission - to lead the board and to make its work effective. If the situation requires it, a good chair is prepared to sacrifice personal interests for the interests of the company – to deal with unpleasant counterparts, to put in as many hours as needed and even to step down from her job.

A good chair knows when and how to leave. She does not designate a successor, but lets the board choose its new leader. The outgoing chair makes her intention to step down known to directors early, leaving enough time (6 to 18 months) to select a successor and to prepare them for the job. The outgoing chair takes time to introduce her future successor to the key stakeholders, passes on information, shares ‘secrets of the house’, but when the new Chairman is elected immediately leaves the stage.

The majority of our participants felt that the programme had helped them to realise that they have the humility and the guts to do what is right, but they admitted to the need to sharpen their listening, challenging and supporting skills. For this, we believe that they had all made another step towards becoming truly good chairs.

Stanislav Shekshnia is an INSEAD Affiliate Professor of Entrepreneurship and Family Enterprise. He is also the Co-Programme Director of Leading from the Chair, one of INSEAD’s Board Development Programmes and a contributing faculty member at the INSEAD Corporate Governance Initiative

This interview with Cees vs Lede, Chairman of the supervisory board of Heineken gives some more insight into the topic.www.youtube.com/watch (browser back button to return to our site)

The Importance of Good Governance

Sth Canterbury Finance: Simpson v. Jenks

The chaotic state of Alan Hubbard’s investment empire was laid bare when a US investor sued to prove her entitlement to $5.5 million. Hubbard’s accounting records were called unorthodox and chaotic and he was described as taking a paternalistic attitude towards his clients without consulting them.

Timaru-based accountant Alan Hubbard had strong local support with his philanthropic activities, but enthusiasm has waned following publicity about the loose way in which he ran his businesses. Government-appointed receivers took control of his business empire in 2010. Mr Hubbard died subsequently in a road accident.

Hubbard’s business activities had two arms: Aorangi Securities Ltd (ASL) which invested primarily in first mortgage securities and Southbury Group Ltd (SGL) which made riskier equity investments in what were perceived to be growth companies.

Receivers’ investigations indicate both ASL and SGL were insolvent by early 2009. They are in the process of realising all assets. Indications are that ASL investors will get back most of their investment; SGL investors very little.

US investor, Susan Jenks was told that her $5.5 million was with SGL. This was a surprise. All the paperwork she held referred to her status as an ASL investor. High Court action followed to clarify where she stood.

The court was told that Mrs Jenks and her husband (who has since died) met Mr Hubbard in 1987 through a mutual connection. On Hubbard’s advice they purchased a Methven farm and made subsequent investments in Christchurch real estate. These investments were rationalised as Mr Jenk’s health deteriorated. The properties were sold and funds left with Mr Hubbard for investment. In October 2009, Hubbard wrote to the Jenks advising their funds had been placed with ASL. Subsequent letters to Mrs Jenks stating the ongoing value of her investment made no reference to the funds having been moved from ASL.

When receivers took control of Hubbard’s business records they found a handwritten journal entry transferring across to SGL Mrs Jenk’s $5.59 million investment in ASL. Justice Dobson said it was extraordinary for a business with $160 million in assets to record the transfer of such an investment with a barely legible handwritten journal entry. The receivers treated this accounting record as proof that Mrs Jenks was a SGL creditor. They refused to accept attempts by Mr Hubbard to reverse the journal entry several months after their appointment. Mr Hubbard claimed the investment had been reversed earlier but he had not completed the paperwork at the time.

Justice Dobson ruled that Mrs Jenks is an ASL investor. As investment adviser to the Jenks and as their agent, Mr Hubbard had no authority to move their funds without their informed consent. Mr Hubbard’s close association with ASL meant the company was liable for his wrongdoing and ASL had to accept that Mrs Jenks was still a creditor.

The court was told that including Mrs Jenks as a creditor of ASL would reduce the payout otherwise available to ASL creditors by about five to six per cent.

Simpson v. Jenks – High Court (20.12.13)

Thanks to Mike Ross Law for this article

Board Decision-making

A January 2013 New South Wales Court of Appeal judgment created a stir in Australian legal and corporate circles about the culture of board decision-making. This from the Chapman Tripp website:

The article was written for the February 2013 issue of Boardroom magazine.

A recent New South Wales Court of Appeal judgment has created a stir in Australian legal and corporate circles about the culture of board decision-making.

At issue was an appeal by former non-executive directors of James Hardie Industries Limited (JHIL) to have their disqualification orders reduced. They had been disqualified from occupying a management or governance role for five years after they were found to have approved the release of misleading information to the ASX.

The evidence to the Court was that, after the meeting had discussed the draft announcement to the ASX, the Board Chairman asked: “Is the board happy with that?” All the directors present had either nodded or remained silent and, as was usual practice for the board, this was taken as sign-off.

One of the Appeal Court Judges (Barrett JA), however, did not consider that the board had satisfied the requirements of section 248G of the Australian Corporations Act and felt moved to comment on what he considered was appropriate procedure, saying:

“Value is often attached to collegial conduct leading to consensual decision-making, with a chair saying, after discussion of a particular proposal, “I think we are all agreed on that”, intending thereby to indicate that the proposal has been approved by the votes of all present.

“Such practices are dangerous unless supplemented by appropriate formality.

“The aim is not to consult together with a view to reaching some consensus, although it may well be, as a practical matter, that such consultation facilitates the making of the decision that is ultimately required. The aim is rather that members of the board should consult together so that individual views may be formed and the individual will of each member may be made known in a clearly communicated way.

“The culmination of the process must be such that it is possible to see (and to record) that each member, by a process of voting, actively supports the proposition before the meeting or actively opposes that proposition; or that the member refrains from both support and opposition. And it is the responsibility of an individual member to take steps to ensure that his or her will is expressed in one of those ways”.

These “observations” were incidental to the decision, but in the opinion of at least one legal commentary, may have “a lasting legacy” on board conduct. Whether these ripple effects make it across the Tasman is hard to predict.

The strong Australian presence in the New Zealand corporate sector would suggest that there may be a roll-on effect. But the default position under the New Zealand Companies Act is different to that in Australia. (In both jurisdictions, the default positions can be contracted out of in a company’s constitution.)

The default position under section 248G of the Corporations Act is that board resolutions “must be passed by a majority of the votes cast by directors entitled to vote on the resolution”. This is not a requirement in the equivalent provisions in Schedule 3 of the New Zealand Companies Act, which state:

• a resolution of the board is passed if it is agreed to by all directors present without dissent or if a majority of the votes cast on it are in favour of it, and

• a director present at a meeting of the board is presumed to have agreed to, and to have voted in favour of, a resolution of the board unless he or she expressly dissents from or votes against the resolution at the meeting. [Emphasis added.]

The New Zealand courts are clear that there is an obligation on each director to read their board papers, make any additional enquiries that are necessary and form their own judgement on the matters before the board. But the New Zealand legislation also permits decisions to be made by acquiescence. Does this suggest that New Zealand law places a higher value on consensus decision-making than Australian law?

Casual readers of the High Court’s judgment last year against the Nathans Finance directors might think so. In that case, the Court criticised the board for not meeting to discuss the final content of the company’s 2006 prospectus and investment statement.

“At such a meeting, the directors could have read through the two offer documents and compared the content with the position they knew existed. Further advice could have been sought on any agreed approach, based on an updated factual position on which the lawyers could advise.

“The absence of a collective discussion meant that the directors “considered” the documents on an individual basis and, in my view, failed to treat the issue with the solemnity it deserved,” the Court said.

The point the Court was making was that the Nathans’ directors were (or should have been) aware that there were serious concerns around Nathans’ exposure to VTL (of which it was a wholly-owned subsidiary) so should have met to discuss and ensure that this risk was presented accurately to the market.

This is not the same thing as consensus. Indeed, the “casual” consensus which arose from the directors’ individual consideration might have been upset had there been a meeting at which the documents were properly discussed. Which is, in essence, the same point being made by Barrett JA in the New South Wales Court of Appeal – directors’ meetings are not merely for the sake of form, but for the purposes of ensuring robust consideration and discussion of proposed courses of action.

New Zealand has a highly consensual governance culture. This is a good thing to the extent that it encourages collegiality. But it can have a downside if directors censor themselves to avoid disturbing the consensus.

The standards to which decision-making directors will be held are the same, however their decisions are made. Whether decisions are made by formal vote or by acquiescence, they should only be made after appropriately robust engagement by all directors.

Geof Shirtcliffe is a partner at Chapman Tripp, specialising in corporate law and governance.

Improving board governance: Latest McKinsey Global Survey results

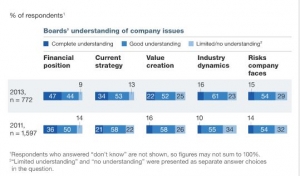

Directors are savvier about strategy than in 2011, still struggle to get their arms around risk management, and can learn more from boards with the highest impact.August 2013

Board directors today are more confident in their knowledge of the companies they serve and more strategic in their approach than they were in 2011, according to the latest McKinsey global survey on governance.1 They say a greater portion of their boards’ time is now spent on strategy, while they are spending less time than before on M&A. The share of time spent on strategy is even greater at private-company boards than at public companies, which tend to spend more time on compliance.

While directors now report a more complete knowledge of various company issues than they did before,2 they say their boards struggle to understand and make time to manage business risks—one of several areas where directors indicate room for further improvement. Another is the clear need for directors to spend more time on their role: the total number of days per year respondents say they spend on board work has not increased much since the previous survey. At boards where directors say their decisions and activities have a very high impact on company performance, though, respondents spend much more time in their role than others do. These directors also report using some best practices (such as resource allocation) that all respondents agree would most improve board performance.

Focusing on strategy

In our previous survey on governance, directors reported incomplete company knowledge, a passive role in strategy, and low overall performance. Now respondents express more confidence overall in their boards’ work and in the amount of influence they wield. When asked about the impact their boards’ decisions and activities have on the companies’ financial success, 73 percent rate this influence as high or very high. Compared with 2011, larger shares of directors say they understand a range of core issues (exhibit). Roughly one-third say they have a complete understanding of current strategy, for example, while just one-fifth said the same two years ago.

Company knowledge is on the rise

Over 90 percent of respondents also say their boards have become more effective over the past five years, most often attributing that improvement to better collaboration with senior executives and more active or skilled independent directors. The views of what drives progress differ somewhat by ownership: 30 percent of directors at publicly owned companies cite more active or skilled independent directors as the primary driver, while just 19 percent of those at private companies say the same.

Across the functional areas of their work, nearly half of directors say that in the past year, their boards have been most effective at strategy, far outpacing all other areas. A board’s strengths can vary by company ownership, too. Though respondents at both public and private companies are most likely to say their boards are most effective at strategy, a much larger share of private-company directors than public-company directors say so (53 percent, compared with 33 percent). Meanwhile, directors at public companies are likelier than their private-company counterparts to say their boards are most effective at compliance (23 percent, compared with 9 percent).

Two reasons may explain why boards are most effective at strategy: board members say they spend more time on it than other areas and that they have increased the amount of overall working time they devote to strategy, answering the call to action expressed by respondents to previous surveys. In our 2008 survey, respondents reported that 24 percent of board time was spent on strategy—and a clear majority said they would increase the time spent.3 Now, directors say their boards spend 28 percent of their time on strategy, and only 52 percent say they would increase it (compared with 70 percent of respondents who said so in 2011). Meanwhile, the share of time spent on execution, investments, and M&A has shrunk, which is likely related to the fact that overall M&A activity has declined since 2007.4

Room for improvement

While respondents say their boards are taking more responsibility for strategy, risk management is still a weak spot—perhaps because boards (and companies) are increasingly complacent about risks, as we move further out from the 2008 financial crisis. This is the one issue where the share of directors reporting sufficient knowledge has not increased: 29 percent now say their boards have limited or no understanding of the risks their companies face. What’s more, they say their boards spend just 12 percent of their time on risk management, an even smaller share of time than two years ago.

Despite the progress they report, directors identify the same factors that would most likely improve board performance as respondents did in the previous survey: a better mix of skills or backgrounds, more time spent on company matters, and better people dynamics to enable constructive discussions. With respect to time, directors say they devote roughly the same number of days to board work as in 2011, and they still want more time. Across regions, directors at North American companies work an average of 22 days on company matters—notably less time than the 29 days and 34 days, respectively, reported by directors at European and Asian companies.

At boards with very high impact, directors spend even more time on their work than their peers at lower-impact boards (40 days per year, compared with only 19 days). Other results suggest that these extra days are not spent on basic compliance but on strategic issues instead. Compared with their peers, the directors at higher-impact boards say they evaluate resource decisions, debate strategic alternatives, and assess management’s understanding of value creation much more often. These respondents are also likelier than others to say their boards ensure that organizational resources are in place to deliver on strategy and that they manage strategic performance.

Looking ahead

Increase attention to risks. According to respondents, most boards need to devote more attention to risk than they currently do. One way to get started is by embedding structured risk discussions into management processes throughout the organization.

Make time. As in 2011, most directors say they want to spend more time on board work, and the results suggest real benefits from doing so: directors at higher-impact boards spend many more days per year on their work than everyone else, which likely helps them stay more relevant to and engaged with important company matters.

Learn from peers. Directors at boards with less impact have much to learn from the actions taken by higher-impact boards, and not only when it comes to strategy. Using robust financial metrics, conducting postmortems of major projects, and using systematic processes to create competitive advantage through M&A—which the high-impact boards do more often—could all help boards become better.